Camera traps capture a wealth of data, offering insights into animal behaviour, population dynamics, and habitat use by wildlife. However, the sheer volume of photos can be daunting, as each one must be carefully reviewed to identify the species captured.

To help with this challenge, the Tasmanian Land Conservancy created WildTracker, enlisting the help of citizen scientists. Still, we know the workload can be overwhelming for landholders! That’s where artificial intelligence (AI) steps in to lighten the load.

We are delighted to introduce Stickybeak. Inspired by the ever-curious currawong, Stickybeak is our AI-powered tool that helps landholders and citizen scientists process thousands of wildlife camera images more efficiently.

Stickybeak recently received two awards at the BETTER FUTURE World Design Awards 2026 – Gold in Environmental Sustainability and Silver in Digital IoT. It has also been featured in several news articles in Tasmania and beyond (read here).

Stickybeak first detects whether an animal, person, or vehicle is present in each camera‑trap image, helping to filter out empty frames often caused by false triggers (e.g., moving shadows or wind‑blown vegetation). This step uses the open‑source MegaDetector, initially developed by Microsoft’s AI for Earth program and now maintained as part of the PyTorch‑Wildlife model zoo. Stickybeak then predicts which species are present in the photos using a model developed by the smart people over at the University of Tasmania – built specifically for our local fauna.

Importantly, citizen scientists remain central to the process. You can accept or reject the AI’s classification or flag a photo for expert review. In doing so, your lovely human brain’s oversight will help us improve the AI model’s accuracy.

Behind the Scenes

Stickybeak has been designed so that any effective wildlife classification model can be ‘plugged in’, ensuring the program remains adaptable in what is a rapidly developing field of technology.

Currently at the heart of StickyBeak is an impressive model developed by researchers from the DEEP (Dynamics of Eco-Evolutionary Patterns) lab at the University of Tasmania. The Mega-efficient Wildlife Classification (MEWC) model uses cutting-edge computer vision techniques to classify wildlife photos. It includes parameters to classify 95 species (or classes, e.g. snakes or insects).

What is Computer Vision?

Computer vision is a field of AI focused on teaching computers to interpret and understand images. By using algorithms like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), computers can analyse images, recognise patterns, and identify objects, similar to how humans process visual information. Applications range from facial recognition systems to medical imaging – and now, wildlife monitoring.

How the MEWC Model Works

The research team at the University of Tasmania leveraged cutting-edge computer vision techniques, inspired by the visual cortex in animals. These techniques involve deep-learning, a subset of machine learning that has revolutionised computer vision. CNNs are a specific kind of deep-learning algorithm designed specifically for processing structured grid data (like pixels), making them powerful for image analysis and enabling computers to learn from vast amounts of training data. These networks mimic the human brain’s visual processing, allowing for highly accurate object recognition, classification, and detection.

Training the model involved feeding it millions of labelled camera trap images where species have been identified by experts. The model learns from these examples, improving its ability to classify new, unseen images accurately. This training process uses a technique called supervised learning, where the model iteratively adjusts its parameters to minimise prediction errors.

The model’s workflow includes four key steps:

1. Detection: After some initial pre‑processing (such as resizing), MEWC begins by running each image through MegaDetector. MegaDetector is an object‑detection model that identifies whether an animal, person, or vehicle is present by producing bounding boxes with confidence scores. If MegaDetector doesn’t detect anything above the confidence threshold, the image is treated as “blank.” In WildTracker, those blank images will be moved to cold cloud storage, where they’ll still exist but won’t clog up our database. Choosing the right detection threshold is one of the trickiest parts: set it too low and you start detecting rocks and tree guards as potential wildlife (false positives); set it too high and you might miss an animal altogether.

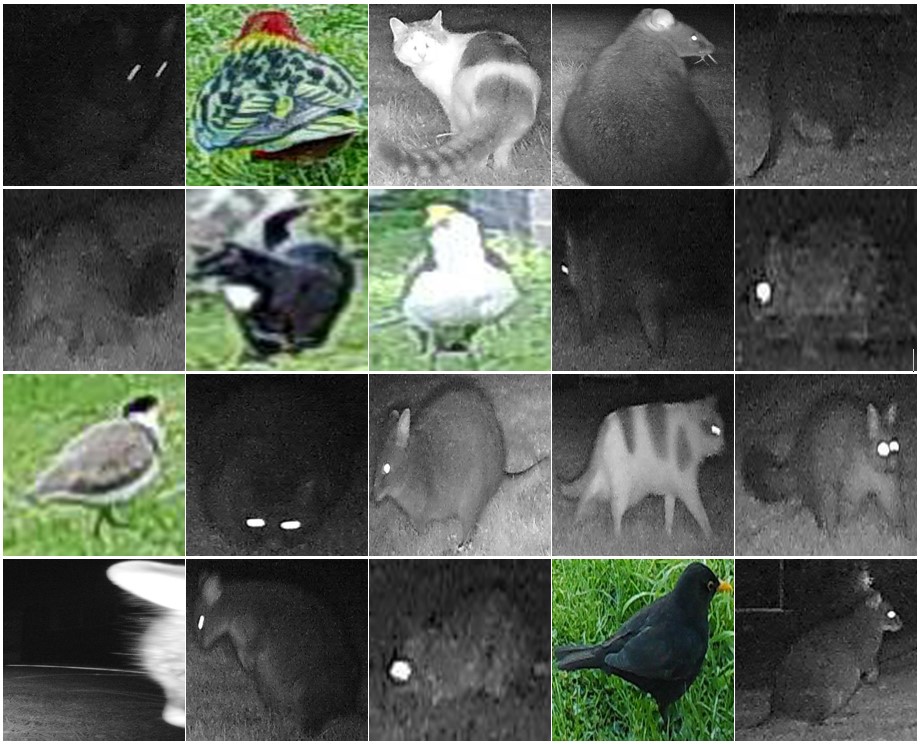

2. Snipping: Features are then extracted from the larger image and resized once more, ready to be classified. The snips below show examples of what the AI “sees” and highlight that these models do not have a sense of scale like we do when classifying species.

3. Prediction: MEWC offers a choice of CNN models to classify each image snip, predicting the species present. It assigns a probability score to each possible species and ranks them accordingly. For example, an object might be predicted with 60% confidence as a pademelon, 30% confidence as a wallaby, 5% confidence as a bettong and so on. This step’s accuracy depends greatly on the quality of training data. Fortunately, MEWC has seen A LOT of Tasmanian animals in different postures, lighting, and coat colours.

4. Annotation: Species classifications and confidence levels are written into the image metadata, enabling WildTracker to display these details alongside bounding boxes from MegaDetector.

As AI technology continues to evolve, the MEWC model and others like it will become even more powerful and accurate. By integrating AI into the WildTracker citizen science program, we have a unique opportunity for human feedback to refine models. WildTracker participants can either accept or reject Stickybeak’s classification or refer it to an expert (one of us ecologists at TLC) for validation. And if you aren’t that confident in your ability to identify species, Stickybeak can provide some helpful hints to get you started.

If all this wasn’t nerdy enough for you, the detailed architecture of MEWC and how it is being deployed can be found in the open access preprint.